Philosophy

Introduction

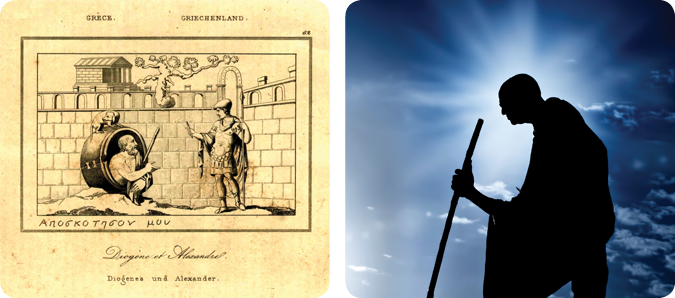

What is the philosophical point of travel? The motivations for human movement have exercised the minds of philosophers across the centuries, among whom fundamental disagreements have arisen about such questions.

A good traveller has no fixed plans and is not intent upon arriving. Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching

Key Aspects

The pleasures of travel

Many philosophers have extolled the benefits of travel. Travel has been praised for:

- Broadening horizons, as well as learning and developing intelligence. For many philosophers, travel is seen as an extension of the journey of life. As George Santayana suggested: ‘What is life but a form of motion and a journey through a foreign world?’ On this basis, philosophers such as Montaigne and Lao Tzu have described the journey as being more important than the destination.

- Providing a means of self-exploration, and a source of memories and experience. As Montaigne argued: ‘Travelling through the world produces a marvellous clarity in the judgment of men… This great world is a mirror where we must see ourselves in order to know ourselves.’

- Improving sociability. Many philosophers, particularly in the Age of Enlightenment, saw the benefits of travel as strengthening human society through the practice of commerce and interaction.

The drawbacks of travel

Other philosophers have questioned the very point of travelling. Key objections have included:

- Travel does not deliver what it promises. Ralph Waldo Emerson believed it was better to stay at home, and that travel was unnecessary for self-development. In his essay Self-Reliance, Emerson wrote: ‘Travelling is a fool’s paradise. Our first journeys discover to us the indifference of places.’

- Travel can be a source of vexation and unhappiness. Gandhi railed against the damaging aspects of modern travel: ‘Is the world any better for quick instruments of locomotion? How do these instruments advance man’s spiritual progress? Do they not, in the last resort, hamper it? Once we were satisfied with travelling a few miles an hour; today we want to negotiate hundreds of miles an hour; one day we might desire to fly through space. What will be the result? Chaos.’

- Travel often necessitates a long time to recover. Today we think of the way jet lag and the crossing of time zones fatigue us; but long voyages across the oceans in cramped ships, or by carriage on miles of unpaved roads also sapped the energies of earlier travellers. ‘Travel is only glamorous in retrospect’, wrote Paul Theroux.

One must always have one’s boots on and be ready to go. Montaigne, Essais (1580)

Practical Implications

- The journey can be more important than the destination. The rewards of travel can arise from the experiences and self-knowledge developed on the way.

- We seek to satisfy many ends when travelling. Policy should show awareness that travel is more than merely getting from A to B.

- There are fundamental reasons not to travel. We should not assume that travel is a panacea; in many cases it can be unnecessary or exhausting.

The soul is no traveller; the wise man stays at home, and when his necessities, his duties, on any occasion call him from his house, or into foreign lands, he is at home still. Ralph Waldo Emerson, Self-Reliance (1841)

Further Reading/Resources

Michel de Montaigne, ed. D. Frame, Travel Journal (1986)

Classic account of Montaigne’s experiences and contemplations during his travels.

George Santayana, ‘The Philosophy of Travel’ from The Birth of Reason and other Essays (1995)

An intelligent exploration of the different range of travel motives.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, Self-Reliance and other Essays (1993)

Emerson describes his philosophy of self-contemplation and antipathy towards travel.

Alain de Botton, The Art of Travel (2002)

Insightful and entertaining philosophical tour through the reasons why we travel.

Key Questions

Do we need to undertake long journeys in order to experience the benefits of travel?

Does travel deliver what it promises?